The Halifax Gibbet

The 'privilege' (right) of a gibbet is believed to have been vested in Halifax around the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066, although the earliest reference to it dates from 1280. At that time, there were said to be one hundred other places in Yorkshire that similarly enjoyed this distinctive honour. In the case of Halifax, however, its notoriety stemmed from the fact that the custom of the Gibbet Law continued long after it had been abandoned elsewhere.

The Laws of Halifax were administered from the Moot Hall (demolished 1957) which stood on a site near the Parish Church in Nelson Street. It was from here that the Lords of the Manor held their court and imposed fines and punishment for a wide variety of offences. Early records show that John de Warren, Earl of Surrey, held court here in 1286. In the same year, the Earls of Warren were granted by the Crown the 'Royalty' to execute thieves and other criminals, from which the Halifax Gibbet Law developed. It was in that first year that John of Dalton was decapitated, the first known victim of the Halifax Gibbet, although formal records of victims did not begin until 1541.

Up to the arrival of the Tudor dynasty in the late fifteenth century, Halifax was little more than a hamlet consisting of some fifteen cottages. However, its strategic position and abundance of clear spring water, made it an ideal location for the fast developing cloth trade. By 1556 the hamlet had grown to more than 500 households, all thanks to cloth manufacture. At that time, the newly manufactured cloth was delivered weekly to the town where it was washed and stretched out on wooden tenterframes and left to dry in the open air. Considering the size of the Halifax trade, the surrounding hillsides would have been covered by row upon row of these frames, leaving exposed and vulnerable the valuable pieces of cloth. And with the cloth reaching high prices, delivery of the bolts became a more and more dangerous occupation. Alarmed at the increase in thefts and at the number that went unpunished, local traders were fearful that the unchecked crime wave could lead to economic damage.

Evidence of the arrival of the gibbet is recorded in Thomas Deloney's "Thomas, of Reading", a romantic and racy ballad in which 'Hodgskins, of Halifax, and his fellow clothiers are represented as having obtained the valuable privilege of the gibbet from the Crown, for the purpose of punishing those who filched their cloth from the tenters.' Local legend goes onto tell of how the good gentlemen of Halifax found it impossible to take on the role of hangman, but that eventually 'a "feat friar" came to the rescue of the tender consciences of the townsfolk, by the timely invention of a "gin" [engine] which was capable of cutting off the heads of "valiant rogues" without the direct intervention of human hands.'

By today's standards, the use of the gibbet was harsh, often being deployed for the punishment of both minor and major offences. Local Gibbet Law dictated that 'If a felon be taken within the liberty of Halifax...either hand-habend (caught with the stolen goods in his hand or in the act of stealing), back-berand (caught carrying stolen goods on his back), or confessand (having confessed to the crime), to the value of thirteen pence half-penny, he shall after three markets...be taken to the Gibbet and there have his head cut off from his body'. While the sum may sound paltry by today's standards, English Common Law at that time permitted the death penalty for thefts to the value of twelve pence and above.

When a thief was caught, he was placed in the custody of the Lord of the Manor's Bailiff. The Bailiff was an important official in that he kept the gaol, the gibbet-axe, and occasionally acted as executioner. Four constables of the Township then met to assess the value of the contraband. If the consensus was that it exceeded the minimum threshold, the Bailiff summoned a jury of sixteen men, usually selected from those who the manor held to be the 'most wealthy and best reputed for honesty and understanding.' Jurors were not put on oath, although their duties hardly required it as they were far from onerous. Their primary responsibility was to identify the goods and confirm its value, and ascertain the means by which the thief (hand-habend, back-berand or confessand). At this point the thief was confronted by the evidence. If he was then acquitted, he was set free after having paid the court fees; if he was condemned, arrangements were made for the execution. Markets occurred on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays: the main market was held on Saturday. These were busy affairs and the spectacle of a decapitation - all beheadings took place at the Saturday market - added to the numbers attending.

After conviction, the felon's fate depended on which day of the week he had been tried. If it took place on a Saturday, he was immediately led to the market place and beheaded. If it was a Monday, he would be kept for three market-days and then beheaded at the next Saturday market. During the intervening days, the prisoner was placed back in the care of the Manor Bailiff and held in gaol. Each day he was taken out and placed in the stocks as a public display of justice being served and as a deterrent to others, often with the contraband placed around him: the stolen cloth would be draped around his shoulders, while stolen animals would be tethered about him.

A curious note on the act of beheading is recorded by the Halifax historian Wright, in which he tells of a country woman on horseback who passed the gibbet while an execution was taking place. At her sides were large wicker baskets, and when the head of the victim was dispatched, the force of the descending axe caused it to bounce a considerable distance "into one of the hampers, or, as others say, seized her apron with its teeth, and there stuck for some time."

A considerably longer description of a decapitation was recorded in Daniel Defoe's account of Halifax in his work "A Tour through the whole Island of Great Britain" (1724-1727). In it he says that 'I must not quit Halifax till I give you some account of the famous course of justice anciently executed here, to prevent the stealing of cloth. Modern accounts pretend to say it was for all sorts of felonies, but I am well assured it was first erected purely, or at least principally, for such thieves as were apprehended stealing cloth from the tenters; and it seems very reasonable to think it was so, because of the conditions of the trial.'

The case to which he alludes was 'the erecting of the woollen manufacture here was about the year 1485 when King Henry VII, by giving encouragement to foreigners to settle in England, and to set up woollen manufactures, caused an Act to pass prohibiting the exportation of wool into foreign parts unwrought, and to encourage foreigners to come and settle here. Of these, several coming over settled the manufactures of various kinds of cloth in different parts of the kingdom, as they found the people tractable and as the country best suited them; as, for instance, the cloth named bays at Colchester; the says at Sudbury; the broadcloth in Wilts and other counties, and the trade of kersies and narrow cloth at this place [Halifax] and other adjacent towns.

When this trade began to settle nothing was more frequent than for young workmen to leave their cloths out all night upon the tenters; and the idle fellows would come in upon them, and tearing it off without notice, steal the cloth. Now, as it was absolutely necessary to preserve the trade in its infancy, this severe law was made, giving the power of life and death so far into the hands of the magistrates of Halifax, as to see the law executed upon them. But the power was not given unless in one of these three plain cases, namely, hand-having, back-bearing, or tongue-confessing.

This being the case, if the criminal was taken he was brought before the magistrate of the town, and those who were to judge and sentence and execute the offender, or to clear him, within so many days. Then there were frithborghs (or jurors) also to judge of the fact, who were to be good and sober men, and by the magistrates of the town to be approved as such. If these acquitted him he was immediately discharged; if those censured (convicted) him nobody could reprieve him but the town. The manner of execution was very remarkable; the engine, indeed, is carried away, but the scaffold on which it stood is there to this time (1727), and may continue for many ages, being not a frame of wood but a square building of stone, with stone steps to go up, and the engine itself was made in the following manner.

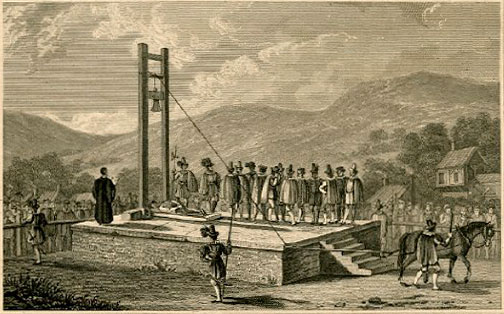

The execution was performed by means of an engine called a gibbet, which was raised upon a platform four feet high and thirteen feet square, faced on every side with stone, and ascended by a flight of steps. In the middle of this platform were placed two upright pieces of timber, fifteen feet high, joined at the top by a transverse beam. Within these was a square block of wood four and a half feet long, which moved up and down by means of grooves made for that purpose; and to the lower part of this sliding block was fastened a sharp iron axe of the weight of seven pounds twelve ounces.

The axe thus fixed was drawn up to the top of the grooves by a cord and pulley. At the end of the cord was a pin, which, being fixed to the block, kept it suspended till the moment of execution, when the culprit, having placed his head on the block, the pin was withdrawn, the axe fell suddenly and violently on the criminal's neck, and his head was instantly severed from his body.' Defoe continued that the force was 'so strong, the head of the axe being loaded with a weight of lead to make it fall heavy, and the execution so secure, that it takes away all possibility of its failing to cut off the head.'

The small number of recorded victims testifies to the success of the deterrent. William Camden's "Descriptions of Britain" (published 1722) records that 'Halifax is becoming famous among the multitude by the reason of a law whereby they behead straightways whosoever are taken stealing'. Its notoriety grew further with the publication of John Taylor's poem of 1622, in which the famous Beggar's Litany 'From Hell, Hull and Halifax, Good Lord deliver us' referred to the notorious strictness of the law enforcers at Hull, the horrors of Hell, and the formidable Gibbet Law at Halifax. Taylor's poem continues:

"At Halifax, the Law so sharpe doth deale,

That whoso more than thirteen pence doth steale,

They have a jyn [engine] that wondrous quicke and well

Sends Thieves all headless unto Heav'n or Hell".

Between 1541 and 1650, the official records show that some 53 recorded persons (men and women) were executed by the Halifax Gibbet.

REGISTER OF PERSONS GIBBETTED AT HALIFAX

1286 John of Dalton

15th January 1539 Charles Haworth

20th March 1541 Richard Beverley of Sowerby

1st January 1542 Unidentified stranger

16th September 1544 John Brigg of Heptonstall

31st March 1545 John Ecoppe of Elland

5th December 1545 Thomas Waite of Northowram

6th March 1568 Richard Sharpe of Northowram

ditto John Learoyd of Northowram

9th October 1572 Will Cockere

9th January 1572 John Atkinson

ditto Nicholas Frear

ditto Richard Garnet

19th May 1574 Richard Stopforth

12th February 1574 James Smith of Sowerby

3rd November 1576 Henry Hunt

6th February 1576 Robert Bairstow alias Fearnside

6th January 1578 John Dickenson of Bradford

16th March 1578 John Waters

15th October 1580 Bryan Casson

19th February 1581 John Appleyard of Halifax

7th February 1582 John Sladen

17th January 1585 Arthur Firth

4th October 1586 John Duckworth

27th May 1587 Nicholas Hewitt of Northowram

ditto Thomas Mason (Vagrant)

13th July 1588 The wife of Thomas Roberts of Halifax

5th April 1589 Robert Wilson of Halifax

21st December 1591 Peter Crabtree of Sowerby

6th January 1591 Bernard Sutcliffe of Northowram

23rd September 1602 Abraham Stancliffe of Halifax

22nd February 1602 The wife of Peter Harrison of Bradford

29th December 1610 Christopher Cosin

10th April 1611 Thomas Brigg

19th July 1623 [?] Sutcliffe

23rd December 1623 George Fairbank

ditto Anna Fairbank, daughter of George Fairbank

29th January 1623 John Lacy of Halifax (He escaped from the execution, but returned 7 years later where he was caught and executed immediately)

8th April 1624 Edmund Ogden of Lancashire

13th April 1624 Richard Midgley of Midgley

5th July 1627 The wife of John Wilson of Northowram

8th December 1627 Sarah Lum of Halifax

14th May 1629 John Sutcliffe of Skircote

20th October 1629 Richard Hoyle of Heptonstall

28th August 1630 Henry Hudson

ditto The wife of Samuel Ettall

14th April 1632 Jeremy Bowcock of Warley

22nd September 1632 John Crabtree of Sowerby

21st May 1636 Abraham Clegg of Norland

7th October 1641 Isaac Illingworthof Ogden

7th June 1645 Jer. Kaye Taylor of Lancashire

30th December 1648 Jo. Wilkinson of Sowerby

ditto Anthony Mitchell

The only way that a condemned person could escape the Gibbet was to withdraw his or her head before the blade fell, and then escape across the parish boundary over the Hebble Brook (*-mile away). The felon could then go free provided that he or she did not return. At least one culprit escaped this way: a man named Dinnis managed the feat, and on his way out of the area was asked by several people if Dinnis was to be beheaded on that day. To his own humour, and the bemusement of the passers-by, Dinnis is said to have replied "I trow not", an expression that is still used by long-term residents of the area. John Lacy also achieved the feat on 29th January 1623, but foolishly returned to Halifax seven years later believing that having made it across Hebble Brook, he was pardoned of his crime that

in any event would have been forgotten. Unfortunately for Lacy, neither assumption was correct and he was duly executed by the gibbet without further trial. The public house "The Running Man" celebrates Lacy's temporary reprieve.

The last recorded victims were the Sowerby men Anthony Mitchell and John Wilkinson. Both men were found guilty of stealing on 19th April 1650, sixteen yards of russet-coloured Kersey from tenterframes owned by Samuel Colbeck of Warley (valued at one shilling per yard) and for stealing two colt horses from John Cusforth of Durker (in the Sandal parish near Wakefield) on 17th April 1650: their total haul was valued at £5.8s. John Wilkinson was additionally convicted of stealing a piece of Kersey from tenterframes at Brearley Hall. As they were found guilty on a Saturday, they were immediately put to death.

After the execution of Mitchell and Wilkinson, the Gibbet was dismantled and the base fell into ruin. There has been speculation that the demise of the device owed much to the public reaction to the beheading of King Charles I during the year before (1649).

The remains of the gibbet base were rediscovered in June 1839, several years after workmen clearing the area had found the skeletons of two men with severed heads - it is assumed that these were the remains of Mitchell and Wilkinson. The Halifax Guardian of the time commented that: 'To the townspeople of Halifax, this relic of more turbulent times will possess many attractions and will no doubt be justly valued by them. As Halifax is the only town in Great Britain rendered famous by such a custom; and since its gibbet is the only one now in existence; this, together with its local association, and the fact that it is the only antique in the town worthy of notice (the parish church excepted) will no doubt ensure its preservation from further decay.'

In 1974 a 4.600 metre high non-working replica was reconstructed on the site. Work was completed on 22nd February of that year, and included a casting taken from the original blade, now preserved in the Pre-Industrial Museum in the glorious Piece Hall. The original weighs seven pounds twelve ounces, and measures almost 260mm in length and 225mm in width.

Text © Andrew Plumridge

The original blade of the halifax gibbet, is on display at Banksfield museum Boothtown Halifax, as the Halifax Industrial museum is now closed.